UNEXPLORED UZBEKISTAN BY SOPHIE IBBOTSON, UZBEKISTAN TOURISM AMBASSADOR TO THE UK

January 29, 2022Uzbekistan is surely an intriguing place to visit, famous for its Silk Route cities of Bukhara, Khiva, and Samarkand. It is double the size of the United Kingdom, and boasts of ancient history and rich cultural heritage.

As Central Asia’s cradle of culture for more than two millennia, it holds a majestic collection of architecture and ancient cities, all deeply infused with the history of the Silk Road. In terms of sights alone, Uzbekistan is arguably the region’s biggest showstopper. The mausoleums of Samarkand, mosques of Bukhara, renowned Savitsky Museum in Nukus housing the greatest art collection in Central Asia, and booming capital Tashkent are just some of the many amazing wonders to discover.

Appointing tourism ambassadors is one of the new approaches Uzbekistan has recently taken to promote the tourism potential of the republic. We asked Uzbekistan’s Tourism Ambassador Sophie Ibbotson to share her insights on Uzbekistan’s rich cultural heritage, it’s Islamic history, and contemporary art and culture.

How did you develop a connection to Uzbekistan and embark on the role of Uzbekistan Tourism Ambassador to the UK?

I have been working in Central Asia since 2008. I’m fascinated by the history and culture, the landscapes, and the people, and have been fortunate enough to work in a variety of roles, including as a consultant to the World Bank and to different governments in the region. Most of what I do involves economic development, and in Uzbekistan tourism is a priority sector. I also wrote Bradt Travel Guides’ guidebook to Uzbekistan. In 2019, I was asked by Uzbektourism (now the Ministry of Tourism and Sports) to become Uzbekistan’s brand ambassador for tourism, representing the country in an official capacity. It was a dream opportunity.

It is said a visit to Uzbekistan is like leafing through the charred chapters of the Silk Road. What are your thoughts on this?

Uzbekistan is the heart of the Silk Road. That’s the first thing tell that to people who are unfamiliar with the country but curious and want a flavour of what it can offer. I’d challenge the idea that those chapters are “charred”, however, because the legacy of the Silk Road is very much alive. Nearly everything about modern Uzbekistan, from the ethnic and cultural makeup of the population to the styles of architecture and food, the languages which are spoken and the trading partnerships which thrive, is the result of the web of economic and cultural ties forged by what we call the Silk Road.

The Islamic architecture adorning the cities of Samarkand, Bukhara and Tashkent are world famous and admired by Muslims and non-Muslims. Can you tell us any interesting information about the architects who constructed and designed these magnificent buildings?

We rarely know the names of the architects who produced Uzbekistan’s monuments; it’s the patrons – the men who paid for the buildings – whose names are usually preserved. There are exceptions, however, such as the 12th century Kalyan Minaret in Bukhara, which was the work of a master architect called Bako. He was an engineer as well as an architect, and went to great lengths to ensure that his minaret survived: he dug foundations 10m deep, and allowed the mortar at the base to settle and dry for two years before he started to build the superstructure. It wasn’t enough for Bako, though. Before he died, he lamented, “The flight of my fancy was greater than the minaret I built.” I’d disagree: 900 years later, the Kalyan Minaret is still standing and it never fails to impress all those who see it.

Although Uzbekistan is most known for its magnificent architecture, what lesser-known aspects of the culture are particularly intriguing?

Uzbekistan’s intangible cultural heritage is wonderful, and the greatest thing about it is that not only are the traditions rooted in thousands of years of history, they are still evolving today. You see this in music and dance, storytelling and food, and also in handicrafts. I love sitting in a workshop and watching artisans weaving, carving, and painting, or listening as the sounds of a doira (drum), rubab (long-necked stringed instrument) or nay (flute) float across the rooftops in an evening.

The country has a rich cultural heritage and history, can you tell us a little about the archaeology of Uzbekistan?

Uzbekistan is a paradise for archeology lovers, especially those with an interest in pre-Islamic history. There are numerous sites dating from the time of Alexander the Great, including his fortress and koriz (subterranean water channels) in Navoi Region, and the city of Alexandria on the Oxus (also known as Kampir Tepe) near Termez. Karakalpakstan alone has more than 50 desert fortresses, many of which have never been excavated, plus the Mizdarkhan necropolis, which I hope will soon be designated as an Archeological Park. There are Buddhist stupas and Zoroastrian towers of silence, petroglyphs of wild animals and hunters, and sites such as Afrosiab (ancient Samarkand) where the most remarkable Sogdian frescoes have been found. As recently as 2019, archeologists surveying the Fergana found evidence of a previously unknown megalithic civilisation with hundreds of ancient burial sites. Every dig season brings more exciting discoveries.

There are many renowned figures from Uzbekistan who have contributed to Islamic history. How is this heritage celebrated and remembered?

The BBC once called Uzbekistan “Land of a thousand shrines.” It is true. So many saints and scholars were born or lived in this region that every village and town seems to have a connection to be proud of. Some of the figures are national heroes with huge memorial complexes: the Imam Bukhari complex near Samarkand and the Bahauddin Naqshbandi mausoleum in Bukhara are the two most famous examples. But I personally love the quiet, smaller shrines, too, where local families have cared for a grave or a sacred spring for centuries.

At a government level, Uzbekistan remembers and celebrates the country’s Islamic heritage and important figures in Islamic history with special events and exhibitions, and in the naming of places and programmes. This winter, the Centre for Contemporary Art in Tashkent held an exhibition called Dixit Algorizmi, which was dedicated to the Persian polymath Muhammad Al-Khwarizmi. A new scholarship programme for 2022, the Imam Bukhari International Scholarship, offers visiting fellowships to postdoctoral scholars researching the lives and scientific legacy of Central Asian scholars and scientists. It is also open to those studying Islamic sciences and manuscripts.

Uzbekistan is one of Central Asia’s most exciting settings. What ways do you hope to bring this to attention to a wider audience?

Uzbekistan is opening up to the outside world again after years of isolation. It doesn’t have the huge PR budgets of the Emirates or Azerbaijan, so we have to build awareness of what the country has to offer slowly and organically.

One of the ways in which we are bringing Uzbekistan to a wider audience is by hosting international events. The Silk Road Literature Festival will be held in Tashkent and Bukhara this year, and the Sharq Taronalari (a world music festival) will take place in Samarkand in August. In 2023, Samarkand will be the host city of the UNWTO General Assembly, so that will definitely cast a spotlight on Uzbekistan’s tourism destinations and culture.

Museums and galleries in Uzbekistan are building relationships with international partners, too. The Savitsky Museum, which has one of the world’s greatest collections of Russian avant-garde art, loaned 100 paintings to the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow in 2017, and recently announced it’ll be sending paintings depicting the Aral Sea to an exhibition in Washington DC. I’m in discussions with the Savitsky’s director, Tigran Mkrtychev, about a future exhibition in London, too.

Can you tell us about the upcoming Second International Festival of Crafts in Kokand. What kinds of crafts will people see and experience?

Kokand is the ideal location for an event of this kind as it is already a World Craft City, a designation given by the World Craft Council. The Fergana Valley in which Kokand is situated is famed for its wood carving, its hand painted ceramics, and its textiles, in particular woven silks, the suzani style of embroidery, and carpet making. Hereditary knife makers like Khasan Umarov make their knives using a technique called Damascus steel, then add intricately decorated bone handles. There are also many workshops producing embroidered skull caps.

The biennial International Handicrafters Festival first took place in 2019, attracting hundreds of participating craftspeople from 78 countries, plus huge numbers of spectators. As with many events, the second festival was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is now scheduled for 10-15 September, 2022. I visited Kokand in November and spoke to the regional administration and local artisans about their preparations.

Woodcarver Jamshid Umarov told me he has already decided which of his products he will submit to the festival’s competitions. He is following his competitors on social media so he knows what he’s up against! I was also delighted to meet Mashkhura Khaidarova, who runs an atelier producing khan atlas (silk ikat). Mashkhura started her business with just one sewing machine and exhibited at the first festival in 2019. She will be back this year, this time presenting the work of her students, most of whom are girls who were previously unemployed. Look out for their traditional designs, but also contemporary wedding dresses and ballgowns.

What about contemporary art and culture in Uzbekistan, which artists should we be looking out for?

The Centre for Contemporary Art is a new institution in Tashkent, which occupies the building of a former power station right in the centre of the capital. The idea is that it’ll become a home for contemporary culture, helping drive its development. One of the first artists to get involved here was Saodat Ismailova, a film maker and multimedia artist who has produced a series of works including 40 Days of Silence, which about four generations of Tajik women living without men; Aral: Fishing in an Invisible Sea; and Qyrq Qyz (Forty Girls), Ismailova’s retelling of a Central Asian epic about a teenage warrior who defends her clan from invaders.

In the last few years I have started collecting contemporary works by several Central Asian artists. I’m a big fan of Alexandr Barkovskiy, and visited the artist in his apartment last time I was in Tashkent. Some images from his Gipsy Madonna series sold at Sotheby’s; they combine photographs of women from Uzbekistan’s luli community, who are often seen begging with their children, with floral motifs, Islamic calligraphy, and sometimes frames made from pieces of beshik, the traditional Uzbek crib. I also have a number of prints by Elyor Nemat, a photographer and print maker who is single-handedly reviving the art of lino cut printing in Uzbekistan. He creates some wonderfully evocative architectural views, and also portraits of cotton pickers.

The third artist I’d like to highlight is Anvar Babaev, a miniaturist from Bukhara. It is thought that Behzad, the famous 15-16th century Persian miniaturist, spent time in Bukhara after the capture of Herat. His atelier inspired generations of artists, and although Anvar lacks a royal patron like Shah Ismail I, he nevertheless produces some exquisite works, including manuscript-style illustrations and calligraphy.

What are your hopes and aspirations for tourism in Uzbekistan and its relationship to the UK?

Tourism in Uzbekistan is growing rapidly; my hope and aspiration is that development will be sustainable economically, environmentally, and socially so that it brings as many benefits as possible to Uzbekistan and to those tourists fortunate enough to visit. The flow of tourists between the UK and Uzbekistan certainly strengthens the relationship between the two countries, not only in physical terms such as the availability of direct flights from London to Tashkent, but also culturally and diplomatically. British tourists visiting Uzbekistan for the first time often have no idea what to expect, but during their trip they are invariably awed by the richness of the cultural heritage and the warmth of the hospitality, as well as by how well-developed and clean Uzbekistan’s cities are. When they return home, they are effusive ambassadors for Uzbekistan, recommending it to their families, friends, and colleagues.

In terms of some specifics for this year, I hope that the action-packed event schedule Uzbekistan has planned can go ahead. I’ve talked about some of the festivals and events already in this interview, but I’d also like to flag up the Lazgi Festival of dance in Khiva, which will be in April; Stihia Festival, which covers electronic music, science and the environment, in Karakalpakstan in May; and the Lavender Festival in Kokand in early June. Events like this showcase the diversity of Uzbekistan’s cultural offering. There really is something for everyone.

What does the future of Islamic art and culture look like to you and how can travel and tourism to Uzbekistan facilitate future opportunities for development?

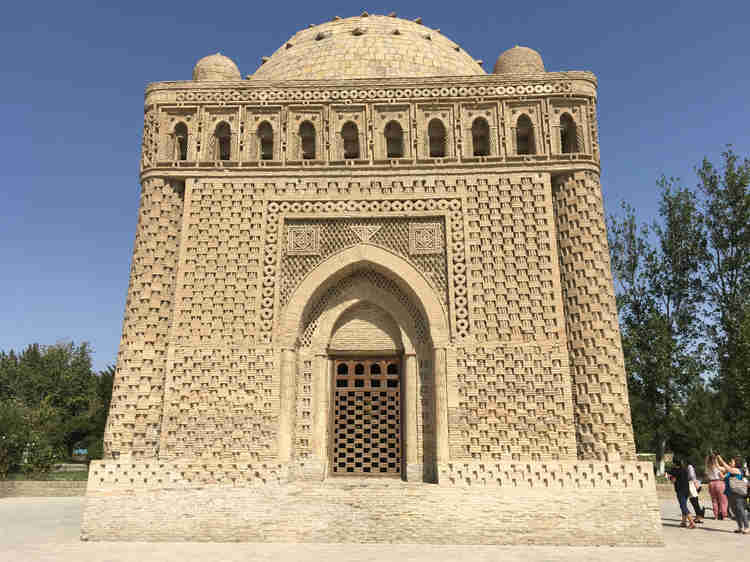

The future of Islamic art and culture is hugely bright in Uzbekistan and beyond. There are 1.8 billion Muslims in the world, a huge proportion of humankind to produce and consume creative works. But the truth is that what we describe as Islamic art and culture aren’t just for Muslims, and they are not solely expressions of an Islamic identity. The Samanid Mausoleum in Bukhara, for example, is recognised as the earliest surviving Islamic monument in Central Asia, but it is the product of multiple cultures: the square shape is reminiscent of a Zoroastrian fire temple, the dome is similar in size and structure to those in nearby Buddhist monasteries, and the decorative motifs include designs from various pre-Islamic cultures. It is a monument which draws upon the very best of human creativity, but finally came to fruition under the patronage of a Muslim patron. This is why the Samanid Mausoleum and so many of Uzbekistan’s other historic monuments are inscribed on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites: they are of outstanding universal value.

Travel and tourism facilitate opportunities for creative development because they open people’s eyes to things which are beyond their previous experience. When we travel, we meet new people, see new things, learn, and challenge our assumptions. What was once regarded as “the other” becomes familiar, and we then engage with it in more positive ways. Uzbekistan is a good example of this, as many of the tourists who visit are coming to a Muslim-majority country for the first time. They arrive with preconceptions about what it will be like, but leave a couple of weeks later with a much more nuanced (and, typically, more favourable) view of both Muslims and Islam as a cultural force. This opens up opportunities for creative discussion and collaboration, and new audiences of art lovers and buyers.

For more information follow Sophie Ibbotson on Twitter https://twitter.com/UZAmbassador

The views of the artists, authors and writers who contribute to Bayt Al Fann do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Bayt Al Fann, its owners, employees and affiliates.